P.O. BOX 1127, EAST ORANGE, NJ 07019

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

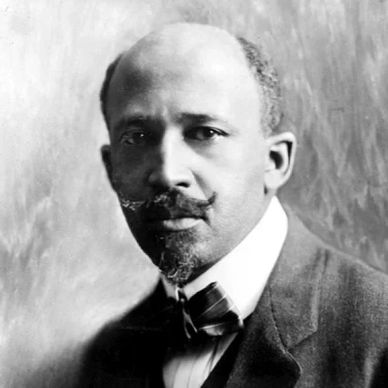

W.E.B. Du Bois was a founding member of NAACP and one of the foremost Black intellectuals of his era. Du Bois published many influential works describing the plight of Black Americans and encouraged Black people to embrace their African heritage even as they worked and lived in the United States.

Before becoming a founding member of NAACP, W.E.B. Du Bois was already well known as one of the foremost Black intellectuals of his era. The first Black American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, Du Bois published widely before becoming NAACP's director of publicity and research and starting the organization's official journal, The Crisis, in 1910.

Du Bois, a scholar at the historically Black Atlanta University, established himself as a leading thinker on race and the plight of Black Americans. He challenged the position held by Booker T. Washington, another contemporary prominent intellectual, that Southern Blacks should compromise their basic rights in exchange for education and legal justice. He also spoke out against the notion popularized by abolitionist Frederick Douglass that Black Americans should integrate with white society. In an essay published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1897, "Strivings of the Negro People," Du Bois wrote that Black Americans should instead embrace their African heritage even as they worked and lived in the US.

Du Bois published his seminal work The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. In this collection of essays, Du Bois described the predicament of Black Americans as one of "double consciousness": "One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder." The term "double consciousness" has come to be widely used as a theoretical framework to apply to other dynamics of inequality.

Du Bois became the editor of the organization's monthly magazine, The Crisis, using his perch to draw attention to the still widespread practice of lynching, pushing for nationwide legislation that would outlaw the cruel extrajudicial killings. A 1915 article in the journal gave a year-by-year list of more than 2,700 lynchings over the previous three decades.

Du Bois, who considered himself a socialist, also published articles in favor of unionized labor, although he called out union leaders for barring Black membership. Under Du Bois's guidance, the journal attracted a wide readership, reaching 100,000 in 1920, and drew many new supporters to NAACP. With Du Bois as its mouthpiece, NAACP came to be known as the leading protest organization for Black Americans. "One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder."

Du Bois served as editor of The Crisis until 1934, when he resigned following a rift with NAACP leadership over his controversial stance on segregation. He viewed the "separate but equal" status as an acceptable position for Blacks. Du Bois also resigned from the NAACP board and returned to Atlanta University.

After a ten-year hiatus, Du Bois came back to NAACP as the director of special research from 1944 to 1948. In this role, he attended the founding convention for the United Nations, channeling his energies toward lobbying the global body to acknowledge the suffering of Black Americans. He wrote the famous NAACP publication, "An Appeal to the World," a precursor to a report charging the United States with genocide for its ugly history of state-sanctioned lynchings. Du Bois also turned a spotlight onto the injustices of colonialism, urging the United Nations to use its influence to take a stand against such exploitative regimes. Throughout his life, Du Bois was active in the Pan-Africanism movement, attending the First Pan-African Conference in London in 1900. He later organized a series of Pan-African Congress meetings around the world in 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927, bringing together intellectuals from Africa, the West Indies, and the United States. At the end of his life, Du Bois embarked on an ambitious project to create a new encyclopedia on the African diaspora, funded by the government of Ghana. A citizen of the world until the end, the 93-year-old Du Bois moved to Ghana to manage the project, acquiring citizenship of the African country in 1961. Du Bois died in Ghana on Aug. 27, 1963, the day before the historic March on Washington.

Mary White Ovington was deeply involved in two of the most important movements of the 20th century: civil rights and women's suffrage. A 1908 article about race riots drove her to rally other thought leaders and activists to start NAACP.

Mary White Ovington was deeply involved in two of the most important movements of the 20th century: civil rights and women's suffrage.

Ovington was born in 1865 in Brooklyn to parents who supported women's rights and the abolition of slavery. As a young woman, Ovington decided to join the civil rights movement after hearing Frederick Douglass speak at a Brooklyn church. Ovington helped to establish the Greenpoint Settlement in Brooklyn and a few years later Greenwich House Committee on Social Investigations in 1904. There, she spent the next five years studying the employment and housing problems of Manhattan's Black community.

Ovington threw herself fully into the cause of civil rights for Black Americans after reading an article in 1908 that described a race riot that led to seven deaths and mass destruction in Abraham Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois. The author, William English Walling, ended the article with a rallying cry to come to the aid of the embattled Black community.

Heeding the call for action, Ovington arranged to meet with Walling, after which they decided to set up a national conference to discuss justice and civil rights for Black Americans. In response, dozens of white activists and seven Black Americans, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells signed a statement that was released on the centennial of Lincoln's birthday on February 12, 1909. A few months later, NAACP held its first meeting. NAACP established a board of directors in 1910, appointing Ovington as NAACP's executive secretary. She later served as the organization's chair after World War I.

Ovington threw herself fully into the cause of civil rights for Black Americans after reading an article in 1908 that described a race riot that led to seven deaths and mass destruction in Abraham Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois.

Ovington combined her civil rights activism with her commitment to the struggle for women's voting rights. In 1921 she wrote to a leading suffragist to request that a Black woman be invited to the National Women's Party's celebration of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. In 1934, Ovington gave a series of speeches to more than a dozen colleges in an effort to demonstrate to Black students that some whites also opposed race discrimination. In these speeches, she would show the map of all of NAACP's branches to show students "the power the race has gained."

Ovington wrote several books about Black society and culture, including Half a Man (1911), Status of the Negro in the United States (1913), a study of Manhattan's Black community, and Portraits in Color (1927), biographical sketches of prominent African Americans. She also documented her work in her autobiography, Reminiscences (1932), NAACP in The Wall Come Tumbling Down (1947). In 1947 after nearly four decades of service she died in 1951 at the age of 86. In 2009, Ovington was depicted on a U.S. postage stamp alongside Black civil rights activist and suffragist Mary Church Terrell.

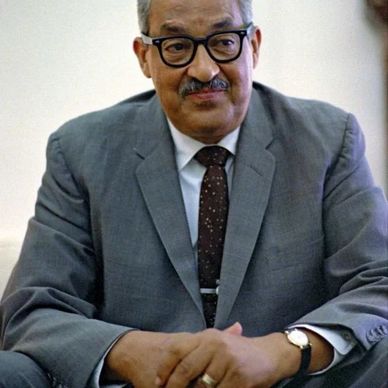

Thurgood Marshall was one of America's foremost attorneys. As chief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, he led the legal fight against segregation, argued the historic 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education, and ultimately became the nation's first Black Supreme Court Justice.

Thurgood Marshall was a civil rights lawyer who used the courts to fight Jim Crow and dismantle segregation in the U.S. Marshall was a towering figure who became the nation's first Black United States Supreme Court Justice. He is best known for arguing the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, in which the Supreme Court declared "separate but equal" unconstitutional in public schools.

A native of Baltimore, Maryland, Marshall graduated from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1930. He applied to the University of Maryland Law School but was rejected because he was Black. Marshall received his law degree from Howard University Law School in 1933, graduating first in his class. At Howard, he met his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston, who encouraged Marshall and his classmates to use the law for social change.

After graduating from Howard, one of Marshall's first legal cases was against the University of Maryland Law School in the 1935 case Murray v. Pearson. Working with his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston, Marshall sued the school for denying admission to Black applicants solely on the basis of race. The legal duo successfully argued that the law school violated the 14th Amendment guarantee of protection of the law, an amendment that addresses citizenship and the rights of citizens.

Soon after, Marshall joined Houston at NAACP as a staff lawyer. In 1940, he was named chief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which was created to mount a legal assault against segregation.

Marshall became one of the nation's leading attorneys. He argued 32 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, winning 29. Some of his notable cases include:

Marshall's most famous case was the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Educationcase in which Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren noted, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

Marshall's civil rights litigation work continues to this day.

President John F. Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. Four years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson named Marshall U.S. solicitor general and on Aug. 30, 1967, Marshall was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and joined the U.S. Supreme Court, becoming the first Black justice.

During his nearly 25-year tenure on the Supreme Court, Marshall fought for affirmative action for minorities, held strong against the death penalty, and supported of a woman's right to choose if an abortion was appropriate for her. The civil rights lawyer turned Supreme Court justice made a significant impact on American society and culture. His mission was equal justice for all. Marshall used the power of the courts to fight racism and discrimination, tear down Jim Crow segregation, change the status quo, and make life better for the most vulnerable in our nation.

MORE HEROES WHO FOUGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

The voices of these visionaries shape our present and inform our future.

A prominent civil rights activist who became the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center, Horace Julian Bond served as chairman of NAACP from 1998 to 2010, bringing the institution into the 21st century. Bond was also active in politics in Georgia, serving in both chambers of the state's government for two decades.

Born in 1940 in Nashville, Tennessee, Bond moved to Pennsylvania as a young boy when his father, Horace Mann Bond, became president of Lincoln University. He returned to the South to attend Morehouse College in Atlanta but soon left school to lead student protests against segregation in Georgia as a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He would return to Morehouse College a decade later to finish his bachelor's degree in English.

Bond was first elected to Georgia's House of Representatives in 1965 along with 10 other Black Americans after voting rights legislation ended disenfranchisement of Blacks. All but a few members of the House refused to seat him, citing his opposition to the Vietnam War. After a district court determined that the Georgia House had not violated Bond's constitutional rights, the case went to the Supreme Court, which overturned the decision and ruled 9-0 in Bond's favor.

In 1998, Bond became chairman of the NAACP, a job he referred to as "the most powerful job a Black man can have in America."

In 1968, Bond led an alternate delegation from Georgia to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where he was nominated as a candidate for Vice President of the United States. Too young to serve, the 28-year-old Bond withdrew his name from the ballot.

Alongside his political career, Southern Poverty Law Center in 1971 as a public interest law firm focused on civil rights issues. He served as its first president for eight years then remained on the board of directors until his death.

Bond served four terms in the Georgia House of Representatives, where he organized the legislature's Black Caucus before he was elected to the Georgia Senate in 1975. He served six U.S. House of Representatives.

After losing to civil rights leader John Lewis, Bond left politics and taught at several distinguished universities, including American University, Drexel University, Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Virginia.

In 1998, Bond became chair of the NAACP board of directors, a job he referred to as "the most powerful job a Black man can have in America." He served for 11 years.

Bond spoke out on important issues of the day through a newspaper column and his frequent appearances on radio and television. He narrated the landmark 14-episode documentary on the civil rights movement, Eyes on the Prize.

Bond published a collection of his essays A Time to Speak, A Time to Act in 1972. Over the course of his lifetime, the civil rights leader received 25 honorary degrees. Bond died in Florida in 2015 at the age of 75.

Throughout his short life, Medgar Evers heroically spoke out against racism in the deeply divided South. He fought against cruel Jim Crow laws, protested segregation in education, and launched an investigation into the Emmett Till lynching. In addition to playing a role in the civil rights movement, he served as the NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi.

Evers began his journey as a civil rights activist when he and five friends were turned away from a local election at gunpoint. He had just returned from the Battle of Normandy in World War II and realized fighting for his country did not spare him from racism or give him equal rights.After attending college at the historically black Alcorn State University in Mississippi and taking a job selling life insurance in the predominantly Black town of Mound Bayou, Evers became president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL). As head of the organization, Evers mounted a boycott of gas stations that barred Black people from using their restrooms, distributing bumper stickers with the slogan "Don't Buy Gas Where You Can't Use the Restroom." annual conferences between 1952 and 1954 in Mound Bayou attracted tens of thousands.

Evers soon turned his sights on desegregation after being rejected from the University of Mississippi Law School because of the color of his skin. The Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education 1954 ruling making school segregation unconstitutional. His fight to desegregate the University of Mississippi Law School bore fruit eight years after he began when James Meredith was enrolled in 1962.As NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi, Evers established new local chapters, organized voter registration drives, and helped lead protests to desegregate public primary schools, parks, and Mississippi Gold Coast beaches.

Evers gained notoriety in the eyes of white supremacists after becoming involved in two high-profile Mississippi cases. His public investigations into the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till and the 1960 conviction of Clyde Kennard, a Black civil rights activist framed for crimes he didn't commit, left Evers vulnerable to attack.White supremacists made several attempts on Evers's life before succeeding on June 12, 1963. After pulling into his driveway and getting out of his car carrying NAACP T-shirts reading "Jim Crow Must Go," Evers was shot in the back and died at the local hospital less than an hour later. He was murdered just hours after President John F. Kennedy's speech on national television in support of civil rights.

After becoming NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi and moving to the state capital of Jackson, Evers established new local NAACP chapters, organized voter registration drives, and helped lead protests to desegregate public primary schools, parks, and Mississippi Gold Coast beaches.

A member of the Ku Klux Klan, Byron De La Beckwith, was arrested for Evers's murder but remained free after all-white juries twice deadlocked on his guilt. Three decades later, justice was finally served when De La Beckwith was found guilty of Evers's murder and sent to prison in his 70s.

Evers was buried with full military honors in front of more than 3,000 people at Arlington National Cemetery. His murder and the failure to convict De La Beckwith inspired a number of songs from popular musicians, including Bob Dylan's "Only a Pawn in Their Game" and "Too Many Martyrs" and "Another Country" by Phil Ochs. The 1996 film The Ghosts of Mississippi starring Alec Baldwin and Whoopi Goldberg depicts the 1994 trial of De La Beckwith for Evers's murder.Evers's family also carried his legacy forward. Both his wife Myrlie Evers-Williams and his brother Charles became prominent civil rights activists, with Myrlie serving as chairwoman of NAACP from 1995 to 1998.

The first general counsel of NAACP, Charles Hamilton Houston exposed the hollowness of the "separate but equal" doctrine and paved the way for the Supreme Court ruling outlawing school segregation. The legal brilliance used to undercut the "separate but equal" principle and champion other civil rights cases earned Houston the moniker "The Man Who Killed Jim Crow."

"This fight for equality of educational opportunity (was) an isolated struggle. All our struggles must tie in together and support one another. . .We must remain on the alert and push the struggle farther with all our might."

Houston's experience in the racially segregated U.S. Army, where he served as a First Lieutenant in World War I in France, made him determined to study law and use his time "fighting for men who could not strike back."

"The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. I made up my mind that if I got through this war I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back."

Houston returned to the U.S. in 1919 and entered Harvard Law School, becoming the first Black student to be elected to the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review. After graduating from Harvard with a Doctor of Laws degree in 1923 and studying at the University of Madrid in 1924, Houston was admitted to the District of Columbia bar and joined forces with his father in practicing law.Later, as dean of the Howard University Law School, Houston expanded the part-time program into a full-time curriculum. He also mentored a generation of young Black lawyers, including Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become a United States Supreme Court justice.

Houston left Howard University to serve as the first general counsel He played a pivotal role in nearly every Supreme Court civil rights case in the two decades before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. Houston worked tirelessly to fight against Jim Crow laws that prevented Blacks from serving on juries and accessing housing.However, it was in the fight against school segregation that Houston came up with the clever argument that would make him famous. His ingenious legal strategy was to end school segregation by unmasking the belief that facilities for Blacks were "separate but equal" for the lie it was.In a 1938 Supreme Court case concerning the admission of a Black man to the University of Missouri, Houston argued that it was unconstitutional for the state to bar Blacks from admission since there was no "separate but equal" facility. At the time, Southern states collectively spent less than half of what was allotted for white students on education for Blacks. Houston's intention was to make it too expensive for facilities to remain separate.

His ingenious legal strategy was to end school segregation by unmasking the belief that facilities for Blacks were "separate but equal" for the lie it was. Houston's shrewd strategy worked, effectively paving the way for desegregation.

While not rejecting the premise of "separate but equal" facilities, the Supreme Court ruled that Black students could be admitted to a white school if there was only one school. Houston's shrewd strategy worked, effectively paving the way for desegregation.

Sadly, Houston would not live to see segregation declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education. He died in 1950 from a heart attack.Houston was posthumously awarded the NAACP Spingarn Medal in 1950 and the main building of the Howard University School of Law was named Charles Hamilton Houston Hall in 1958. Harvard Law School named a professorship after him and in 2005, opened the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice.

A key figure of the Harlem Renaissance, James Weldon Johnson was a man of many talents. Not only was he a distinguished lawyer and diplomat who served as executive secretary at NAACP for a decade, he was also a composer who wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing," known as the Black national anthem.

Born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida, Johnson was heavily influenced by his mother, who passed on her love of music and literature, interests that would follow him throughout his multifaceted career. After graduating in 1894 from Atlanta University, a historically Black college, Johnson returned to Jacksonville and taught at the Stanton elementary school for Black students. Once he became principal, Johnson expanded the school to include high school education.While at Stanton, he also began studying law and in 1898 became the first Black man admitted to the Florida Bar since Reconstruction. While balancing his dual career in education and law, Johnson still found time to write poetry and songs, including "Lift Every Voice and Sing," to honor Abraham Lincoln's birthday.

In 1901, Johnson moved with his brother, a composer, to New York City to write for musical theater. Together, they composed about 200 songs for Broadway. In New York, Johnson began making connections to influential members of the Black community, leading to the next stage of his career in diplomacy.After serving as treasurer for the Colored Republican Club, Johnson was sent to become the United States consul in Venezuela by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906. Three years later, he was moved to Nicaragua to serve as consul. During this time, Johnson continued to write poetry and anonymously published his novel, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912), a story of a young biracial man living in the post-Reconstruction era.

Johnson left the diplomatic world to join the civil rights movement in 1916 as a field secretary for NAACP, where he helped open new branches and expand membership. He also campaigned for a federal anti-lynching bill and spoke at the 1919 National Conference on Lynching. In 1920, Johnson became NAACP executive secretary, a position he used to fight against segregation and voter disenfranchisement in South.

Johnson believed Black Americans should produce great literature and art in order to demonstrate their equality to whites in terms of intellect and creativity.

Johnson held the top position at NAACP for a decade before resigning to teach creative writing at Fisk University in Nashville, a position created in recognition of his achievements as a writer and his standing as a leading light in the Harlem Renaissance.

Through the course of his wide-ranging career, Johnson developed a unique philosophy on achieving equality for Blacks and combating racism, one that stood in contrast with views espoused by W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. While Du Bois argued for steeping oneself in a liberal arts education and Booker T. Washington advocated for industrial training, Johnson believed Black Americans should produce great literature and art to demonstrate their equality to whites in terms of intellect and creativity.Johnson died in 1938 at the age of 67 in a car accident. He had established his place within the Harlem Renaissance with The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, republished in 1927, his poetry collection God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927), and the anthology he compiled and edited, The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922).

No figure is more closely identified with the mid-20th century struggle for civil rights than Martin Luther King, Jr. His adoption of nonviolent resistance to achieve equal rights for Black Americans earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. King is remembered for his masterful oratorical skills, most memorably in his "I Have a Dream" speech.

Born in 1929 in Atlanta, Georgia, King was heavily influenced by his father, a church pastor, who King saw stand up to segregation in his daily life. In 1936, King's father also led a march of several hundred African Americans to Atlanta's city hall to protest voting rights discrimination.As a member of his high school debate team, King developed a reputation for his powerful public speaking skills, enhanced by his deep baritone voice and extensive vocabulary. King left high school at the age of 15 to enter Atlanta's Morehouse College, an all-male historically Black university attended by both his father and maternal grandfather.After graduating in 1948 with a bachelor's degree in sociology, King decided to follow in his father's footsteps and enrolled in a seminary in Pennsylvania before pursuing a doctorate in theology at Boston University. While studying for King served as an assistant minister at Boston's Twelfth Baptist Church, which was renowned for its abolitionist origins. In Boston, he met and married Coretta Scott, a student at the New England Conservatory of Music.

After finishing his doctorate, King returned to the South at the age of 25, becoming pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Shortly after King took up residence in the town, Rosa Parks made history when she refused to give up her seat for a white passenger on a Montgomery bus.Starting in 1955, Montgomery's Black community staged an extremely successful bus boycott that lasted for over a year. King, played a pivotal leadership role in organizing the protest. His arrest and imprisonment as the boycott's leader propelled King onto the national stage as a lead figure in the civil rights movement.

"Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.… We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed." — Martin Luther King, Jr.

With other Black church leaders in the South, King founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to mount nonviolent protests against racist Jim Crow laws. Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's model of nonviolent resistance, King believed that peaceful protest for civil rights would lead to sympathetic media coverage and public opinion. His instincts proved correct when civil rights activists were subjected to violent attacks by white officials in widely televised episodes that drew nationwide outrage. With King at its helm, the civil rights movement ultimately achieved victories with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

In 1959, King returned to Atlanta to serve as co-pastor with his father at the Ebenezer Baptist Church. His involvement in a sit-in at a department 1960 presidential election between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy. Pressure from Kennedy led to King's release.Working closely with NAACP, King and the SCLC turned their sights on Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, organizing sit-ins in public spaces. Again, the protests drew nationwide attention when televised footage showed Birmingham police deploying pressurized water jets and police dogs against peaceful demonstrators. The campaign was ultimately successful, forcing the infamous Birmingham police chief Bull Connor to resign and the city to desegregate public spaces.

"There is nothing greater in all the world than freedom. It's worth going to jail for. It's worth losing a job for. It's worth dying for. My friends, go out this evening determined to achieve this freedom which God wants for all of His children." — Martin Luther King, Jr.

During the campaign, King was once again sent to prison, where he composed his legendary "Letter from Birmingham Jail," in response to a call from white sympathizers to address civil rights through legal means rather than protest. King passionately disagreed, saying the unjust situation necessitated urgent action. He wrote: "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.… We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."

In 1963, King and the SCLC worked with NAACP and other civil rights groups to organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which attracted 250,000 people to rally for the civil and economic rights of Black Americans in the nation's capital. There, King delivered his majestic 17-minute "I Have a Dream" speech.Along with other civil rights activists, King participated in the Selma-to-Montgomery march in 1965. The brutal attacks on activists by the police during the march were televised into the homes of Americans across the country. When the march concluded in Montgomery, King gave his "How Long, Not Long" speech, in which he predicted that equal rights for African Americans would be imminently granted. His legendary words are widely quoted today: "How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."Less than six months later, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act banning disenfranchisement of Black Americans.

Over the next few years, King broadened his focus and began speaking out against the Vietnam War and economic issues, calling for a bill of rights for all Americans.In the spring of 1968, King visited Memphis, Tennessee, to support Black sanitary workers who were on strike. On April 4, King was assassinated by James Earl Ray in his Memphis hotel. President Johnson called for a national day of mourning on April 7. In 1983, Congress cemented King's legacy as an American icon by declaring the third Monday of every January Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

"The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." — Martin Luther King, Jr.

King was honored with dozens of awards and honorary degrees for his achievement throughout his life and posthumously. In addition to receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, King was awarded the NAACP Medal in 1957 and the American Liberties Medallion by the American Jewish Committee in 1965. After his death, King was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and received the Congressional Gold Medal in 1994 with his wife, Coretta.King's legacy has inspired activists fighting injustice anywhere in the world. NAACP has carried on King's work on behalf of Black Americans and strives to keep his dream alive for future generations. We take inspiration from his closing remarks at the NAACP Emancipation Day Rally in 1957: "I close by saying there is nothing greater in all the world than freedom. It's worth going to jail for. It's worth losing a job for. It's worth dying for. My friends, go out this evening determined to achieve this freedom which God wants for all of His children."

"In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.… America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked 'insufficient funds.'"

-- Martin Luther King, Jr.

The country's first major Black filmmaker, Oscar Micheaux (sometimes written as "Michaux"), directed and produced 44 films over the course of his career. Throughout the first half of the 20th century Micheaux depicted contemporary Black life and complex characters in his films, countering the negative on-screen portrayal of Blacks at the time.

Born in 1884, Micheaux tried his hand at a number of vocations before embarking on a film career. Moving to Chicago from a small Illinois town when he was 17 years old, Michaeux shined shoes and worked in the meatpacking and steel industries before landing a job as a porter for the American railway system. This stable job allowed him to travel, save money, and make connections with wealthy people who later helped finance his films.

Operating in the first half of the 20th century, Micheaux depicted contemporary Black life and complex characters in his films, countering the negative on-screen portrayal of Blacks at the time.

In 1904, Michaeux moved to South Dakota and became a successful homesteader amid a predominantly blue-collar white population. The government's Homestead Act allowed citizens to acquire a free plot of land to farm. Although the act included Black Americans, discrimination kept many Blacks from pursuing a homestead. Michaeux began writing about his experiences on the frontier, submitting articles to the press as well as writing novels.

Published in 1913, his first novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer was loosely based on his own life as a homesteader and the failure of his marriage. The novel attracted attention from a film production company in Los Angeles, which offered to adapt the book into a film. Negotiations fell apart when Michaeux wanted to be directly involved in the film's production, and he decided to produce the film himself.

After setting up his own film and book publishing company, Michaeux released The Homesteader in 1919. The silent black-and-white film features a Black man who enters a rocky marriage with a Black woman, played by the pioneering African American actress Evelyn Preer, despite being in love with a white woman.

Depicting realistic relationships between Black and white people, the film gained praise from critics, one of them calling it a "historic breakthrough, a creditable, dignified achievement." Micheaux followed up his successful production with his second film, Within Our Gates (1920), which sought to challenge the heavy-handed racist stereotypes shown in D.W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation.

Micheaux used his films, the first by a Black American to be shown in white movie theaters, to portray racial injustice suffered by Black Americans, delving into topics such as lynching, job discrimination, and mob violence. Given the restrictions of the time, Micheaux's prolific career was nothing short of groundbreaking. The acclaimed filmmaker died in 1951 at the age of 67 while on a business trip.

Harry T. and Harriette Moore, a Florida couple active in the civil rights movement, paid the ultimate price for the freedoms won for their community when they were killed by Ku Klux Klan members in their own home in 1951. By the time of their death, Florida had the highest number of registered Black voters, far more than any other Southern state.

Born in the Florida Panhandle, Harry was sent to live with his three aunts in Jacksonville, home to a large and vibrant Black community. His aunts, two of them teachers, nurtured his love of learning, and the few years Harry spent with them would prove pivotal to his racial and political awakening.

After graduating from high school, Harry became a fourth-grade teacher at a Black elementary school in Brevard County. There, he met Harriette Vyda Simms, a former schoolteacher who was selling life insurance. After marrying, the couple completed their college education at Bethune Cookman College, a historically Black university, and eventually returned to teaching.

In 1934, the Moores founded a chapter of the NAACP in Brevard County. Initially, Harry kept his job as a teacher, working in an unpaid capacity for NAACP for more than a decade. He fought tirelessly for equal rights for Black Floridians by investigating lynchings, challenging barriers to voter registration, and advocating for equal pay for Black teachers in public schools despite segregation.

By the time of their death, Florida had the highest number of registered Black voters, far more than any other Southern state.

Harry and Harriette were eventually fired from their teaching jobs because of their activism, at which point Harry became a paid NAACP organizer. Eventually, Harry was appointed executive secretary for the Florida NAACP. During his tenure at the helm of the Florida branch, statewide membership grew to a peak of 10,000 members in 63 branches.

With the help of NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall, in 1937 Harry filed the first lawsuit in the South calling for Black and white teacher salaries to be equal. Although the initial lawsuit failed in state court, it generated a dozen other federal lawsuits that eventually led to equal salaries in Florida.

After the Supreme Court ruled in 1944 that all-white primary elections were unconstitutional, Harry registered 31 percent of eligible Black voters, adding 116,000 members over six years to the Florida Democratic Party.

Harry grew deeply involved in the 1949 Groveland rape case, in which four young Black men were accused of raping a white woman. Following the arrests of three of the men, a white mob of more than 400 people rampaged through Groveland's Black neighborhood, leading authorities to call out the National Guard to restore order.

After an all-white jury convicted the men and sentenced them to death, Harry led a successful campaign to overturn the wrongful convictions. In 1951, the Supreme Court granted the appeal and ordered a new trial. While driving two of the defendants to a pre-trial hearing, the town's sheriff shot them, killing one and critically injuring another. Harry called for the sheriff's suspension and indictment for murder.

Six weeks later, on Christmas night, a bomb exploded under the bed of Harry and Harriette Moore. It was the couple's 25th anniversary. The first-ever NAACP official to be assassinated, Harry died on the way to the hospital, while Harriette died in the hospital nine days later.

Despite a nationwide outcry and a massive FBI investigation, no one was arrested for the couple's killing. It took more than half a century before the case was reopened and four Ku Klux Klan members were identified as being directly involved in the murders.

Langston Hughes composed a poem, "The Ballad of Harry Moore," in the wake of the couple's death, and in 1952, NAACP awarded Harry the Springarn Medal for outstanding achievement by an African American.

After the initial outcry, the couple's story faded from history for a few decades but interest in their lives enjoyed a revival in the 21st century. Several landmarks in Brevard County bear their name, including a park, a justice center, a highway, and a post office. Their home was also declared a Florida Heritage Landmark.

Rosa Parks occupies an iconic status in the civil rights movement after she refused to vacate a seat on a bus in favor of a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1955, Parks rejected a bus driver's order to leave a row of four seats in the "colored" section once the white section had filled up and move to the back of the bus.

Her defiance sparked a successful boycott of buses in Montgomery a few days later. Residents refused to board the city's buses. Instead they carpooled, rode in Black-owned cabs, or walked, some as far as 20 miles. The boycott dealt a severe blow to the bus company's profits as dozens of public buses stood idle for months. The boycott was led by a newcomer to Montgomery named Martin Luther King, Jr.

At the time, Parks led the youth division at the Montgomery branch of NAACP. She said her anger over the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till and the failure to bring his killers to justice inspired her to make her historic stand. Four days before the incident, Parks attended a meeting where she learned of the acquittal of Till's murderers.

In her autobiography, Rosa Parks: My Story (1992), Parks declares her defiance was an intentional act: "I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was 42. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

As a result of her defiance, Parks was arrested and found guilty of disorderly conduct. NAACP joined her appeal, a case that languished in the Alabama court system. Segregation on public buses eventually ended in 1956 after a Supreme Court ruling declared it unconstitutional in Browder v. Gayle. Parks was not included as a plaintiff in the decision since her case was still pending in the state court.

"I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was 42. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in." — Rosa Parks

In addition to her arrest, Parks lost her job as a seamstress at a local department store. Her husband Raymond lost his job as a barber at a local air force base after his boss forbade him to talk about the legal case. Parks and her husband left Montgomery in 1957 to find work, first traveling to Virginia and later to Detroit, Michigan.

Parks supported the militant Black power movement, whose leaders disagreed with the methods of the nonviolent movement represented by Martin Luther King. Her break with other Montgomery leaders over the future of the civil rights struggle contributed to her departure from the Southern city.

Parks was struck by the similarity in treatment of African Americans in Detroit, finding that schools and housing were just as segregated as they were in the South. She joined the movement for fair housing and lent her support to local candidate John Conyers in his bid for Congress.

After he was elected in 1965, Conyers repaid the favor by employing Parks as his secretary in his Detroit office, a position she held until her retirement in 1988. In the role, Parks worked with constituents on issues such as job discrimination, education, and affordable housing.

Parks remained active in the civil rights movement in the 1960s and helped investigate the killing of three Black teenagers in a 1967 race riot in Detroit.

Over the course of her life, Parks received many honors, including NAACP's Springarn Medal in 1979, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996, and the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999. After Parks died in Detroit in 2005 at the age of 92, she became the first woman to lie in honor in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C.

California, Missouri, Ohio, and Oregon commemorate Rosa Parks Day every year, and highways in Missouri, Michigan, and Pennsylvania bear her name.

Roy Wilkins spent more than four decades at NAACP and held the top job at the civil rights organization for 22 years, beginning in 1955.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1901, Wilkins grew up with his aunt and uncle in St. Paul, Minnesota. While attending the University of Minnesota, he worked as a journalist at the Minnesota Daily and the St. Paul Appeal, a Black newspaper where he served as editor. After graduating with a degree in sociology, he became the editor of the Kansas City Call in 1923, a weekly newspaper serving the Black community of Kansas City, Missouri.

His journalism turned into activism as he challenged Jim Crow laws, and in 1931, he moved to New York City to become the assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White. Three years later, he replaced W.E.B. Du Bois as editor of The Crisis, NAACP's official magazine.

In 1950, Wilkins cofounded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, a coalition of civil rights groups that included the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council. The coalition has coordinated the national legislative campaign behind every major civil rights law since the 1950s.

"The players in this drama of frustration and indignity are not commas or semicolons in a legislative thesis; they are people, human beings, citizens of the United States of America." — Roy Wilkins

In 1955, Wilkins was named NAACP executive secretary (a title later changed to executive director), holding the position until 1977. One of his first actions at the helm of the organization was to support the Black-owned Tri-State Bank in Memphis, Tennessee, in granting loans to Blacks who were being denied loans at white banks.

Wilkins helped organize the historic March on Washington in August 1963 and participated in the Selma-to-Montgomery marches in 1965 and the March Against Fear in Mississippi in 1966. Under Wilkins's direction, NAACP played a major role in many civil rights victories of the 1950s and 1960s, including Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act.

A staunch believer in nonviolent protest, Wilkins strongly opposed militancy as represented by the Black power movement in the fight for equal rights. He wanted to achieve reform through legislative means and worked with a series of U.S. presidents toward his goals, beginning with President John F. Kennedy and ending with President Jimmy Carter. In 1967, Wilkins was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Lyndon Johnson.

After stepping down as NAACP executive director in 1977 at the age of 76, Wilkins was honored with the title NAACP Director Emeritus. His autobiography Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins was published in 1982, a year after his death. In his book he calls for treating Black Americans with dignity, writing, "The players in this drama of frustration and indignity are not commas or semicolons in a legislative thesis; they are people, human beings, citizens of the United States of America."

His legacy lives through the center named after him, the Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice, established in 1992 at the University of Minnesota's Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. The military honored his contributions with the Roy Wilkins Renown Service Award, given to members of the armed forces who embody the spirit of equality and human rights.

Known as the "Father of " Carter G. Woodson was a scholar whose dedication to celebrating the historic contributions of Black people led to the establishment of Black History Month, marked every February since 1976. Woodson fervently believed that Black people should be proud of their heritage and all Americans should understand the largely overlooked achievements of Black Americans.

Woodson overcame early obstacles to become a prominent historian and author of several notable books on Black Americans. Born in 1875 to illiterate parents who were former slaves, Woodson's schooling was erratic. He helped out on the family farm when he was a young boy and as a teen worked in the coal mines of West Virginia to help support his father's meager income. Hungry for education, he was largely self-taught and had mastered common school subjects by the age of 17. Entering high school at the age of 20, Woodson completed his diploma in less than two years.

Woodson worked as a teacher and a school principal before obtaining a bachelor's degree in literature from Berea College in Kentucky. After graduating from college, he became a school supervisor in the Philippines and later traveled throughout Europe and Asia. In addition to earning a master's degree from the University of Chicago, he became the second Black American after W.E.B. Du Bois Harvard University. He joined the faculty of Howard University, eventually serving as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

After being barred from attending American Historical Association conferences despite being a dues-paying member, Woodson believed that the white-dominated historical profession had little interest in Black history. He saw African-American contributions "overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."

For Black scholars to study and preserve Black history, Woodson realized he would have to create a separate institutional structure. With funding from several philanthropic foundations, Woodson the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 in Chicago, describing its mission as the scientific study of the "neglected aspects of Negro life and history." The next year he started the scholarly Journal of Negro History, which is published to this day under the name Journal of African American History.

Woodson came to believe that African-American contributions "were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."

Woodson's devotion to showcasing the contributions of Black Americans bore fruit in 1926 when he launched Negro History Week in the second week of February to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Woodson's concept was later expanded into Black History Month.

Woodson died from a heart attack at the age of 74 in 1950. His legacy lives on every February when schools across the nation study Black American history, empowering Black Americans and educating others on the achievements of Black Americans.

Throughout the course of his life, Woodson published many books on Black history, including the A Century of Negro Migration (1918), The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 (1919), The History of the Negro Church (1921), and The Negro in Our History (1922).

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.